History, Reconciliation, and Form: A Conversation

Between Amaud J. Johnson & Douglas Kearney

Between Amaud J. Johnson & Douglas Kearney

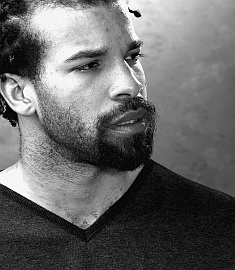

Amaud Jamaul Johnson is a native son of Compton, California.

His first book, Red Summer (Tupelo, 2006), was selected by Carl

Phillips as winner of the 2004 Dorset Prize. He is a former Wallace Stegner

fellow at Stanford University, and a graduate of the Cave Canem workshop.

His work appears in the Virginia Quarterly Review, Shenandoah, and

New England Review. He teaches in the MFA Program at The University

of Wisconsin-Madison.

|

Douglas Kearney is a poet and performer and teacher.

His poetry has appeared in journals including Callaloo, nocturnes,

jubilat, Gulf Coast and others; as well as several anthologies,

including The Ringing Ear, Role Call, the World Fantasy

Award-Winning Dark Matter: Reading the Bones and Saints

of Hysteria which features a collaboration between Kearney and Harryette Mullen.

He has written and performed for a number of audio recordings as well as for television. He has been a featured performer at venues across the country, including the New York Public Theater, the Orpheum in Minneapolis, Locus Arts in San Francisco and the World Stage in Los Angeles and has received commissions from the Weisman Art Museum in Minneapolis and the Studio Museum in Harlem to create poetry in response to art installations. His first full-length collection of poetry, Fear, Some was published by Red Hen Press in October 2006. |

Douglas Kearney: Amaud, in reading Red Summer, I got a feeling of coherence that made me think, “oh! this book is a project more than a collection.” A lot of folks suggest that poets are obsessive and so a focus on a single theme or event happens organically and has less to do with imposing a set of rules upon a manuscript than just thoroughly investigating a preoccupation. So:

What was the drive behind Red Summer? Were there poems you didn’t include or didn’t write because they didn’t address the violence we see in the book; or, perhaps it’s better to ask: when did your poetry begin to become your manuscript?

What was the drive behind Red Summer? Were there poems you didn’t include or didn’t write because they didn’t address the violence we see in the book; or, perhaps it’s better to ask: when did your poetry begin to become your manuscript?

Amaud J. Johnson: Without question poets are obsessive; I’m obsessive; I think this is one of the core characteristics all artists share. It could even be said that poets are obsessive-compulsive, but let me stop before I start talking about my mother. The question regarding the “project book” is a complicated one, partially because most poetry collections have unifying elements. Does Ashbery have a project? Did Stevens and Williams have projects? Well, much of that might be folded into a poet’s aesthetic values. What it means to complete a book of poems is to establish some kind of cohesiveness. Poetry isn’t about answering questions, necessarily, but maybe, after several poems, we’ll begin to ask better questions, or get somewhere closer to truth (at least a version of the truth). That said, maybe my experience growing up in the Los Angeles inner city makes me hesitate to say my book, Summer, “lives in the projects.” At the same time, my preoccupation with race, violence and historical trauma gave shape to the collection. Thinking about the history of race riots in this country, I had trouble understanding the root causes that inspired hatred and ignited such unspeakable violence, both white against black and black against white. The summer of 1919 was one of the most turbulent periods in United States history between the Civil War and the Civil Rights movement. Over 26 riots occurred across this country in an eight-month period. I was as much interested in the lives of the people involved in these riots as the spectacle of violence; the aesthetics of violence. I realized this could be a book when I couldn’t stop thinking about it. Writing Red Summer was part intellectual investigation, part spiritual/emotional journey, and part exorcism. Again, obsessions. We write to satisfy a curiosity, but also to just be free of the damn thing.

Allow me turn the tables: in your book, Fear, Some, from allusions to Zip Coon, Aunt Jemima, and Buckwheat to a poem that re-enacts a minstrel show, you have incorporated multiple voices and many shifting masks. The metaphor of mask and the function of the trickster figure are, of course, central in discussions of African American literature and culture. How significant were these concepts as you sat down to write this book? It seems that rather than double consciousness, many of your speakers are both blessed and cursed with triple, sometimes quadruple perspectives or personalities. W.E.B Dubois argued that it was “dogged strength” that held the individual together. Your speakers seem much more volatile, much more fragile. What lurks on the other side of this frustration and this sense of alienation? And do you believe poetry is the best vehicle to explore these concerns?

Allow me turn the tables: in your book, Fear, Some, from allusions to Zip Coon, Aunt Jemima, and Buckwheat to a poem that re-enacts a minstrel show, you have incorporated multiple voices and many shifting masks. The metaphor of mask and the function of the trickster figure are, of course, central in discussions of African American literature and culture. How significant were these concepts as you sat down to write this book? It seems that rather than double consciousness, many of your speakers are both blessed and cursed with triple, sometimes quadruple perspectives or personalities. W.E.B Dubois argued that it was “dogged strength” that held the individual together. Your speakers seem much more volatile, much more fragile. What lurks on the other side of this frustration and this sense of alienation? And do you believe poetry is the best vehicle to explore these concerns?

DK: Good question, and it’s something I don’t think we’ve talked about in much detail before, which is funny, because it’s so important to me. The trickster figure is perhaps my central preoccupation. I think I’m drawn to the idea that the trickster troubles things out of a kind of hunger and that in some cases, you can’t tell whose side the trickster is on. I believe it’s important for poets to constantly question—so I completely understand your writing as a mode of inquiry (which reminds me, I owe you that Fred Moten book). That questioning—particularly of institutions and relationships which folks, for whatever reason, take for granted—rhymes with a trickster fooling an enemy or a friend. The important thing for the trickster to remember, though, is that troubling the order is not necessary something for which we are rewarded. In art, however, there is sometimes a kind of distance the audience can adopt at which point, the trick becomes pleasurable, or at least intriguing. In sequencing Fear, Some, I wanted to make the reader suspicious of me. To question my motivations. I believed this would make the reader more active, to really examine the words.

But back to your question, the multiple masks are things Dubois could not, perhaps, truly anticipate. The range of possibility in social positioning for black people just wasn’t there. I feel we betray our complexity and cripple ourselves when we limit our perception to a kind of binary. Yet, multiple masks can lead to a certain social and then personal disintegration. That’s the tension I’m after. I’m not interested in masking myself into humanity; I’m already human. But I am interested in how these voices can interact in individual psyches–particularly in the psyches of African Americans–in hopes that it will give me a clearer understanding of these voices in the macrocosm. Poetry works well for this because I don’t have to think in terms of story. I can think in terms of moment or incident or, hey, think in terms of thinking.

I’ve been working on an idea. You and I both seem engaged by the intersection of violence and entertainment. I’m thinking of your “Burlesque” where a burning becomes a striptease, “Aesthetics” or “The Manassa Mauler” and your new poems which I can’t wait to see out in the world. Is that an L.A. thing? A black L.A. thing? Your poetry travels the country and travels through time, but do you identify an L.A. dynamic?

But back to your question, the multiple masks are things Dubois could not, perhaps, truly anticipate. The range of possibility in social positioning for black people just wasn’t there. I feel we betray our complexity and cripple ourselves when we limit our perception to a kind of binary. Yet, multiple masks can lead to a certain social and then personal disintegration. That’s the tension I’m after. I’m not interested in masking myself into humanity; I’m already human. But I am interested in how these voices can interact in individual psyches–particularly in the psyches of African Americans–in hopes that it will give me a clearer understanding of these voices in the macrocosm. Poetry works well for this because I don’t have to think in terms of story. I can think in terms of moment or incident or, hey, think in terms of thinking.

I’ve been working on an idea. You and I both seem engaged by the intersection of violence and entertainment. I’m thinking of your “Burlesque” where a burning becomes a striptease, “Aesthetics” or “The Manassa Mauler” and your new poems which I can’t wait to see out in the world. Is that an L.A. thing? A black L.A. thing? Your poetry travels the country and travels through time, but do you identify an L.A. dynamic?

AJJ: I like to think that I’m not a violent person. I’ve never been in a fistfight, and only one person in my family has hit another person in anger (whippings not included, of course). This was a badge of honor for my grandmother, who rose more than her share of boys. But as you know, L.A., particularly in the late 80s and early 90s, up until the 92 Riot, L.A., some parts at least, were like living in Beirut. I remember weekend murder counts that ran like lottery numbers on the evening news. And the violence was so random: babies, old women, people sitting on bus stops, walking out of the grocery store, anyone, any day could die. This was also the tail end of the Cold War, and as a kid growing up in Compton, I figured if the Bloods didn’t kill me the Bolsheviks would. And when I went to church, the preacher kept letting on that “we were in the Last Days,” and that we needed to “get right with our maker.” I think when you get close enough to death, like getting close to any object, you start to lose sight of the whole, and start looking at particulars. In time you become de-sensitized to violence. With the poems you mentioned, “Burlesque” and so on, I wanted to write about the spectacle of violence. Based on what I grew up around, and what I’ve learned about the nature of genocide, average citizens, people who, on the surface are loving, soft-spoken, church-going, middle of the road kinds of folk, are capable of some of the worst acts imaginable. Rather than undress the body by violence, I think I wanted to undress the audience. I want to place the readers in a position where they have to question themselves. I’m not pointing the finger at anyone. But at the same time, I’ll be damned if anyone thinks he or she will get off the hook. Good or bad, our whole history is writing in blood.

I’m glad you mentioned LA because it’s always been so hard for me to write about. When I think about L.A., I think about family and neighborhood, but with the music industry, Hollywood, and the Valley (referring to the porn industry), home feels a little like the scene of a crime. It’s interesting how race and geography figure in your work. Poems like “Alameda Street,” “Orange Alert,” and “Rallying” occupy intimacy, even when rage is near. In other poems, “Anthem (Collapsing)” and “Atomic Buckdance,” the voice explodes. With all these masks, and here masking comes in the form of voice, structure, and music, is there space for self-reconciliation? How do you see this holding together as a collection?

I’m glad you mentioned LA because it’s always been so hard for me to write about. When I think about L.A., I think about family and neighborhood, but with the music industry, Hollywood, and the Valley (referring to the porn industry), home feels a little like the scene of a crime. It’s interesting how race and geography figure in your work. Poems like “Alameda Street,” “Orange Alert,” and “Rallying” occupy intimacy, even when rage is near. In other poems, “Anthem (Collapsing)” and “Atomic Buckdance,” the voice explodes. With all these masks, and here masking comes in the form of voice, structure, and music, is there space for self-reconciliation? How do you see this holding together as a collection?

DK: For me, arrival at self-reconciliation is only possible through pulling out all your masks and letting them clash with each other, thus the explosions of voice. Remember when I called you to tell you I smashed all of my Miles Davis CDs to protest Davis’ abuse of women? I’m the same guy who once balled his fist to threaten his grandmother and often looks at pornography (did I tell you, I’ve moved to the Valley?). There was a time I wrote to create veils, which is just a kind of hiding—masking the mask. I try to avoid that now. We can’t help writing in persona at some level or else our poem (because we would each write only one) would be a continuous stream of language, pre-language and actually disconnected imagery (not artfully disconnected). What interests me, in some poems, is revealing the mask(s). The mask isn’t itself a lie, it’s a piece of a larger truth, and as such, tells us a great deal. That’s at the microcosmic, poem by poem level. The collection plays at this idea of revealing mask after mask by placing a poem like “Alameda Street” next to a poem like “Pastime.” It forces the questions, is this mask a product of this mask? Is it the same mask, but from a different angle? The final poem, “The Poet Writes The Poem That Will Certainly Make Him Famous” is me flinging open my wardrobe and throwing masks out in front of my guests. I don’t know that self-reconciliation is a final thing. Every day offers us the opportunity for new conflict, new ideas. We are constantly faced with experiences and perceptions to integrate or reject, to reconcile this newness with our sense of self. If the book has dogged strength, it’s in its commitment to being unsettled, to be at some levels protean, but aware of the ultimate limits of that mutability. I can write about misogyny, I can be critical of it. But I can never forget my own complicity and my own practice of it. Self-reconciliation does not censor or disintegrate, it accepts flaws and, hopefully, seeks to correct them, right?

AJJ: How do you feel about the label “experimental poet”?

DK: I don’t mind it all. I am trying stuff and seeing what works for me. I am interested in seeing how much tension I can create between recognizable tropes and the particular music in my head. I won’t split hairs because I understand the intent behind the tag, “experimental” but a lot of us are trying things or at least think we are trying to do stuff that hasn’t happened just so before. And many of these folks wouldn’t consider themselves or be generally considered experimental. I read an interesting essay by William Gass in which he suggests that experimental art ought to function like experimental science, you do it to see what kind of result you get and then, that act is no longer an experiment because you know what happens. I think that’s a fine way of thinking of it. For me, it’s a bit more self-conscious; I don’t want to feel like I’m getting by on flash or gimmicks, so I try to mutate the dynamics and nonce forms I create, building on “past discoveries” if you will, and up the ante. I become a skeptic of my own proofs, flounce my own constraints. What’s the label for that?

Carl Phillips called you a “restorative” poet. I read that as suggesting your work delves into history and attempts to return fragments as whole. How do you interpret the restorative function? Do you see that as a role you are comfortable with?

Carl Phillips called you a “restorative” poet. I read that as suggesting your work delves into history and attempts to return fragments as whole. How do you interpret the restorative function? Do you see that as a role you are comfortable with?

AJJ: Well, I think history is fragmented. It does move in a linear fashion. I know we were taught to memorize a series of dates and important names connected to those dates. We were taught to look at timelines, and retrace footsteps. But I find rumor and misinformation just as interesting. I want to write poems that salvage those details that defy categorization. I’m looking for lost or lesser know artifacts, which may be physical or emotional. I worked as an archivist before writing Red Summer, and one of the most frustrating and wonderful aspects of the job was learning how to label the items we received. I would sift through old suitcases and boxes full of scrap pieces of paper and photographs. I was my job to create a narrative, the arc of someone’s life. In the process of developing this skill, I fell in love with things like receipts or shopping lists; it was ephemeral, but I think our lives, our personal histories are made up of the accumulation of junk. When I write I’m trying to bring those things to the surface. I’ve never thought about it in this way, but I guess that makes my work restorative.

Speaking of history, I’m curious about your influences. What significance, if any, does the legacy of the Black Arts Movement have on your work? I’m thinking of the role of politics, race consciousness, African American cultural memory and the idea of a Black Aesthetic.

Speaking of history, I’m curious about your influences. What significance, if any, does the legacy of the Black Arts Movement have on your work? I’m thinking of the role of politics, race consciousness, African American cultural memory and the idea of a Black Aesthetic.

DK: Great question. These issues are on my mind a lot recently. I’m supposed to have a public talk/reading with Amiri Baraka in November. Crazy, right? A lot of those folks were of course, iconoclasts at the very least and I’m interested in that. Not just to tumble down what came before me, but to make the poetry of my time truly of that moment. It would be easy to imitate the clichés that developed from the movement as it is easy to do so with what comes out of every movement—in the performance poetry world, where I’m rooted, you see that a lot.

The four elements you mention are of great importance to me. I’m obsessed with the political as a landscape. I was on a panel where an artist mentioned that he felt the political was outside of art, that it didn’t enter his practice organically but was a kind of external process. I said that for me, the political is a part of how I see the world, that my art making doesn’t begin without realizing who I am and what it means for me to be writing a poem and not doing something else. The poetic tradition itself is a contentious space and it does me no good to go through it blithely, that damn thing will eat you!

On cultural memory, a brief anecdote. In high school, I was going to a conference for black youth. I had on a Malcolm X shirt, an Africa-medallion, a kente crown—before I got out the door, my mother stopped me and told me I didn’t have to dress my way into blackness, I was already there. I say that to say, my mom and dad were two southerners who met in NY. They lived in Brooklyn before moving to Altadena, CA. My idio-mimeo-vault is full of enough articles of cultural memory that I needn’t dress up my poems, I just have to occupy them. Part of that is because of what the Black Artist Movement already put into poetry.

Black aesthetics are still not generally accepted in the mainstream, tolerated maybe, but, like anything that attempts to show black folks in our wholeness, our aesthetics are marginalized, our interests unfashionable. Whatever. I’m fascinated by what Black Experiences produce. I’m fascinated by our relationships with the English language, that it’s something to be distrusted, bent, manipulated, remade for our purposes.

Of course we have our own intra-mainstream as well. Our own set of clichés. I think I try to resist reducing myself into that space with equal rigor.

Whom are you reading these days and are you reading them for something in particular?

The four elements you mention are of great importance to me. I’m obsessed with the political as a landscape. I was on a panel where an artist mentioned that he felt the political was outside of art, that it didn’t enter his practice organically but was a kind of external process. I said that for me, the political is a part of how I see the world, that my art making doesn’t begin without realizing who I am and what it means for me to be writing a poem and not doing something else. The poetic tradition itself is a contentious space and it does me no good to go through it blithely, that damn thing will eat you!

On cultural memory, a brief anecdote. In high school, I was going to a conference for black youth. I had on a Malcolm X shirt, an Africa-medallion, a kente crown—before I got out the door, my mother stopped me and told me I didn’t have to dress my way into blackness, I was already there. I say that to say, my mom and dad were two southerners who met in NY. They lived in Brooklyn before moving to Altadena, CA. My idio-mimeo-vault is full of enough articles of cultural memory that I needn’t dress up my poems, I just have to occupy them. Part of that is because of what the Black Artist Movement already put into poetry.

Black aesthetics are still not generally accepted in the mainstream, tolerated maybe, but, like anything that attempts to show black folks in our wholeness, our aesthetics are marginalized, our interests unfashionable. Whatever. I’m fascinated by what Black Experiences produce. I’m fascinated by our relationships with the English language, that it’s something to be distrusted, bent, manipulated, remade for our purposes.

Of course we have our own intra-mainstream as well. Our own set of clichés. I think I try to resist reducing myself into that space with equal rigor.

Whom are you reading these days and are you reading them for something in particular?

AJJ: I’m usually all over the place with reading lists. This week I’ve lined up John Berryman, Jane Hirshfield, Greg Pardlo, Patricia Smith, Maurice Manning, Terrance Hayes, Elizabeth Bishop, Tim Seibles, Brigit Pegeen Kelly and some history books on Vaudeville. I like poetry buffets. I’ll spread them all out on a big table, and then dig in. Sometimes I read with a craft question in mind, such as “what is the relationship between the line and the sentence,” or “the relationship between the image system and the music of a poem.” Sometimes I’m trying to cover gaps. Sometimes, I’m hoping to fall in love with poetry again.

DK: When was the last time you stopped loving poetry and who, to bite Regina Bell, “Made it like it was”?

AJJ: Regina Bell! We are beginning to date ourselves. Next thing you know we’ll start quoting Peabo Bryson and Bobby Womack. But this brings up an important idea related to your question: nostalgia. Sometimes, I’ll fall in love with a poet or a poem and I’ll close ranks, creating my little artistic love nest. I had this with Robert Hayden, Jean Toomer, Gwendolyn Brooks and Yusef Komunyakaa at different points. It’s not that the love doesn’t last, but the nature of my relationship with their work changes as I grow as an artist. I start to feel nostalgic for that first experience with a poem. Didn’t Dickinson describe the feeling of reading a great poem as if the top of your head has been blown off? I read many wonderful writers, but it’s rare that I’m consumed by a poem. Out of frustration, I begin to think that maybe all the great poems have been written. (This includes my writing). Then I come across something like Terrance Hayes’ Wind in a Box or Tomas Tranströmer’s The Great Enigma. It’s like music. Great songs are great songs, but if you listen to the radio long enough, it will make you sick, it will make you hate music. At the same time if you think the only great bands were the Chi-lites and the Delfonics, or Salt n Pepper and the LA Dream Team, that nostalgia can breed a form of hatred.

DK: I hear you. I get curious, though, about what a song, or trend in songs I don’t like, answers for its audience. I am at war with myself on whether when it comes to pop culture, the consumer gets the art they “deserve” or if the culture is determined by marketers. I know it’s more complicated than that, but once I’m done cussing at the radio, I start to think bout what’s happening dynamically between the song and its listener. I wonder whether it’s structural, content-based or contextual—all three, etc. Then I wonder how one can remix those dynamics.

Anyway, there’s a poem I’ve been struggling to write for years. It’s connected to the L.A. Riots from 1992. I grew up in a white church and I had choir practice as parts of L.A. burned only 20 miles from me. I remember standing in the parking lot, alone, and imagining a group of angry black folks showing up and asking–it’s ridiculous–but asking if there were white people in the building. I’ve never been able to figure out what I would say, you know; whose Judas would I be? Is there a poem that’s haunted you, that every now and then you put your skill to?

Anyway, there’s a poem I’ve been struggling to write for years. It’s connected to the L.A. Riots from 1992. I grew up in a white church and I had choir practice as parts of L.A. burned only 20 miles from me. I remember standing in the parking lot, alone, and imagining a group of angry black folks showing up and asking–it’s ridiculous–but asking if there were white people in the building. I’ve never been able to figure out what I would say, you know; whose Judas would I be? Is there a poem that’s haunted you, that every now and then you put your skill to?

AJJ: Thinking of the Riots, there was a poem I really struggled with myself. I remember the first sunset of the curfew, how beautiful it was. I used to love going to the beach or sitting on top of the roof of our house to watch sunsets. It was so strange to live in a space where that was illegal, even for a few days. I also remember in the months after everything settled, how the gaps where the burnt out buildings once stood seemed like missing teeth. Talk about urban decay. But it’s so hard to write about home. I keep wanting everything to turn out differently. All poems are personal, but I’ve seen some things that I still haven’t found the words for. Those emotions are in everything I write; hell, Compton is what I breathe, it’s mixed up in my bread. It might be interesting to try a collaborative piece?

DK: I’d love that. Westside English! Although it couldn’t hope to be better than our improvised love jones poems.

AJJ: It could get dangerous. I’m starting to remember Cross cords, wearing Boulevards, and drinking Super Socco and Gin. Hell, I might try to grow back my Jheri curl. Don’t hate.

Doug, on a more serious note, one can’t help but notice how your poems are formatted; with lines ascending or deciding into each other. I wouldn’t call your work concrete poetry, however, you are obviously extremely conscious of form. Could you say something about the relationship between structure and your subject matter in Fear, Some?

Doug, on a more serious note, one can’t help but notice how your poems are formatted; with lines ascending or deciding into each other. I wouldn’t call your work concrete poetry, however, you are obviously extremely conscious of form. Could you say something about the relationship between structure and your subject matter in Fear, Some?

DK: Aw, man, I’m just trying to make it look the way it sounds in my head. Really, my background is in performance and there was (for a time, and probably still) this dyad of “stage” and “page.” Like I said in reference to Dubois, I think things are usually more interesting, more complicated than binaries, so I became fascinated with the idea of using the page as a performance space. I went to CalArts where there’s a lot of discussion about interdisciplinarity. I wanted to take what I knew about poetics and, say, graphic design and try to figure out the dynamics of certain poetic devices. Rhyme, for instance—how does one rhyme visually? Or how can one create relationships without exposition? “Atomic Buckdance” is full of visual characterizations accorded each voice. I use italics as a kind of characteristic forging a connection between all the italicized voices in the poem; I do the same thing with boldface and capitalization. The ascending and descending you mention is there to suggest things I don’t want to dilute the poem by writing in the poem; instead, the lines enact certain orientations and conflicts. The different combinations of typeface and positioning in that poem tell you about how I think the Two Head is related to the Trickster and how the Victim is related to the Authority and the Singer. It was tempting to do that in every poem, but I’ve come to think of the typographic effects as any other device. I try to give each poem what it needs. Some of them need the page to do more than just cradle couplets along the left margin. That being said, once you start considering these visual relationships they have a way of opening a lot of more subtle doors. “(dig!) Bloom is Boom, Sucka!!!” is actually full of these ideas, just not as immediately noticeable as in “The Chitlin Circuit” or “Atomic Buckdance.” But The Black Automaton poems (from my new manuscript), they blow down walls for me in terms of what the page can do. I remember thinking when I finished my first Automaton poem: “This is either the best thing I’ve done or the most ridiculous.” It could be both!

What are you working on?

What are you working on?

AJJ: As we speak, I’m working on a series of poems loosely connected to Black Vaudeville. Since Red Summer addresses spectacles of violence, to move in the opposite direction, I’ve been thinking about humor; specifically how laughter exposes our cultural make up as Americans. This project branches off into different directions including early film, dance, burlesque and poetry. Today, I’m working on poems about Lincoln Perry (aka Stepin Fetchit) and Butterfly McQueen, who played Prissy in Gone with the Wind. I’m more interested in the actors’ lives than the characters they played. I’m interested in stepping into their masks, and hopefully in the process I can learn more about my own. I’m very excited about where this is leading.

What do you have on your plate?

What do you have on your plate?

DK: Man, I just finished the second manuscript. It’s called The Black Automaton. As I mentioned, my typography stuff in this one is a bit different from the first book, really interrogating how we read things and attempting to synthesize some ideas I have about hip hop culture and its relationship to language—whether sampled or in a wildstyle. I’m interested in where process and form meet content; the idea of automatons makes a sense of construction appropriate, I think. Plus, the fact that automatons are often artificial human beings allows me to investigate everything from stereotypes, to persona poems, to infertility. But that, I guess, is technically off my plate. I’m in the break, so to speak, the echo of my last obsessions are just starting to fade, and I have my sticks over the skins waiting to hit.

AJJ: Last Question: How has the role of the Black poet changed in recent years? Do you feel that you are a part of something larger, a new movement maybe? The number of collections written by African American poets in bookstores today, prize-winning poets, amazes me.

DK: Big questions. I’ll start with the one about movements. We’ve both graduated from Cave Canem, which is, of course, a significant group; I hesitate to call it movement in that Cave Canem articulates itself as an environment and even the most superficial look at the range of poetics of CC fellows will reveal that while the organization has a mission, the poets follow their own paths. But before CC, for you and I at least, there was Howard University. When someone takes Yona Harvey’s excellent manuscript, I’ll feel like I’m a part of a movement as I see interesting parallels in our work and perhaps it’s because the three of us were at HU at the same time. I can see myself in the context of hip hop poetry, but because I believe a poem has to do more than just reference hip hop or be in a rap style to qualify, I don’t know that people see the same movement I would like to see. I mean, if all one has to do is mention, say, rap music, Tony Hoagland is a hip hop poet. But whatever.

The role of the Black poet? I don’t know that the role has changed. I imagine there isn’t agreement that a single role exists and if so, what is it? The tools with which to function as a Black poet have certainly changed. Whether we’re speaking about technology—word processing programs are not able to do everything I need my poetry to do. Aesthetics—as dead prez say, “it’s bigger than hip hop,” but as an example, hip hop itself has changed in texture with the changing laws and economy of sampling, regional shifts and the rise of the “super producer” commodity. And of course, we’ve added cultural memories—Katrina, 9/11, Dave Chappelle’s satire, genocide in Rwanda, the spread of A.I.D.S. in our communities and the Continent, another war in the Middle East.

For me, the role that exists outside of the marketing aspects of publishing is Black poets must continue to examine the world with an eye on where and how we each occupy it. I think a poet accomplishes this by being willing to be rigorously honest. For example, pretending to be a militant revolutionary is as faulty as pretending to be “a-poet-who-happens-to-be-Black.” Writing the poem about or that enacts why one would feel the need to pretend either way is the space that needs more exploration, narrative, critique. We need to turn all our masks over in our hands. It would be problematic for me to insist on what the outcome of these individual poems would be; I know I don’t have all of the answers. But I think that basic process is right and when practiced with real rigor won’t be strictly confessional, myopic or wanly ambiguous. I think it’s the way to give our contemporary poetry actual dogged strength.

My Last Question for you: What do you think the role of the Black poet is?

The role of the Black poet? I don’t know that the role has changed. I imagine there isn’t agreement that a single role exists and if so, what is it? The tools with which to function as a Black poet have certainly changed. Whether we’re speaking about technology—word processing programs are not able to do everything I need my poetry to do. Aesthetics—as dead prez say, “it’s bigger than hip hop,” but as an example, hip hop itself has changed in texture with the changing laws and economy of sampling, regional shifts and the rise of the “super producer” commodity. And of course, we’ve added cultural memories—Katrina, 9/11, Dave Chappelle’s satire, genocide in Rwanda, the spread of A.I.D.S. in our communities and the Continent, another war in the Middle East.

For me, the role that exists outside of the marketing aspects of publishing is Black poets must continue to examine the world with an eye on where and how we each occupy it. I think a poet accomplishes this by being willing to be rigorously honest. For example, pretending to be a militant revolutionary is as faulty as pretending to be “a-poet-who-happens-to-be-Black.” Writing the poem about or that enacts why one would feel the need to pretend either way is the space that needs more exploration, narrative, critique. We need to turn all our masks over in our hands. It would be problematic for me to insist on what the outcome of these individual poems would be; I know I don’t have all of the answers. But I think that basic process is right and when practiced with real rigor won’t be strictly confessional, myopic or wanly ambiguous. I think it’s the way to give our contemporary poetry actual dogged strength.

My Last Question for you: What do you think the role of the Black poet is?

AJJ: I think about what Wheatley faced, what Dunbar faced, what Hayden and Brooks faced. “Yet do I marvel at this curious thing”! It seems like we have always been at war for so long; physical and psychological war with others, and within ourselves. Yet we sing. It’s both hope and rage. I mean, we are not “out-of-the-water”, but ultimately poetry is survival, the need to breathe. I’m not a political poet, but at the same time, I believe everything is political. In my early twenties, maybe during my graduate work in African American Studies, I made my peace with my role in this struggle. I’m too moral to be a politician and not moral enough to be a preacher (or should that be reversed). Poetry is how I engage history and tradition. I carry all these lives and voices in my back pocket. I have “black poet” on my Wisconsin license plate (no I don’t). But this is the box I’ve checked. When I’m writing, I’m home.