REVIEW

Austin Kleon’s Newspaper Blackout

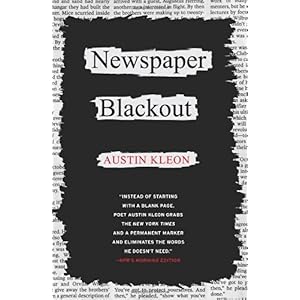

Newspaper Blackout by Austin Kleon

Harper Perennial, 2010 (208 pages)

ISBN: 978-0061732973

Harper Perennial, 2010 (208 pages)

ISBN: 978-0061732973

When I sat down to read Newspaper Blackout by Austin Kleon, I was skeptical, yet fascinated. Kleon had taken a permanent marker to the daily newspaper, blacking out all words but the few he needed to create a poem on the page. I thought, instantly, of my first box of magnetic poetry bought at an art museum while I was still in high school. If we write poetry with magnets, why not with newspaper articles?

Really, Kleon’s project is nothing new. Kleon owns up to this in the book’s introduction though he insists he wasn’t aware of any “artistic or poetic precedent” when he started this project. “As it turns out,” Kleon discloses, “there’s a 250-year-old

history of folks finding poetry in the daily newspaper.” Kleon gives credit where it’s due and traces this history from English wine merchant Caleb Whitefoord’s “cross-readings” of newspapers in the 1760s to William Burroughs’ “cut-ups.” He also gives a hearty nod to contemporary artists obsessed with remixes and mash-ups.

Today’s “remix culture” presents Kleon with a perfect opportunity to re-introduce the concept of “cut-up” poems: he has a pre-made audience who is used to seeing mash-ups and collages everywhere from popular television shows like Glee to radio pop songs to books like Pride and Prejudice and Zombies.

The more pages I turned in Newspaper Blackout, the less skeptical I became. First of all, the visual effect of the poems here is very captivating—we’re so used to seeing the words of a poem float like fragile black birds on the big, white lake of the page. The poems here appear instead as negatives of the poetry we’re used to. The background is black and the words appear less like delicate fowl and more like a smattering of white bricks on blacktop. For the sake of clarity, I’ve not replicated the spacing of the poems in the excerpts here; the words sprawl across the page in these poems.

With few poems longer than thirty words, Kleon’s poems are brief enough to capture even the shortest attention span. This brevity, coupled with down-to-earth subject matter, result in poems that are extremely accessible. Spanning teenage awkwardness to navigating a new marriage, Kleon’s poems are rooted in familiar terrain and often take a look at the lighter side of life. “Pure Emo” pokes good-natured fun at the “Whitest Kids U’Know.” In “Tetherball,” the speaker surmises that if you had a bad nickname

you d

hit

the

tetherball,

mercilessly

As a collection, Newspaper Blackout is very well-organized—poems are often grouped by subjects, one flowing into the next. Subject matter seems to increase in complexity as the reader moves through the book. The first poems in the collection are cute, but it’s the poems in the second half of the book which show a poignancy and relevancy that is surprising for poems put together from words on a newspaper page. A series of poems looks at the relationship between husband and wife. Another captures the existential crisis of the speaker. One of those, “Who Put Me Here?,” questions the origins of humankind.

it seems a little brutal

some sort of supernatural man

with the

power-

to

fashion

his

Fantasy

My favorite poems of Newspaper Blackout are the ones about relationships—this is where Kleon seems most natural and his technique most effective. In “Smile,” the speaker, armed with a camera and trying to be funny, teases:

at some point you have to

Smile

The character of Meg (likely Kleon’s wife) appears in “Slow Dance.” Meg and the speaker go to a dance and are irked by the country music that’s playing when they arrive:

Dang-it

no!”

I was here

for “Slow Dancing”

(“whereas” creates a sentence fragment. I suggest replacing it with a transitional word or simply getting rid of it) However, “Slow Dance” captures a funny, simple moment between two people, “As a Frog” considers the complexity of a developed romance. In this poem, the words are connected by little lines, reminiscent of ladders, making for especially easy reading.

s, he

liked him more

as a Frog

in

her small

soft,

hands

Austin Kleon closes the book with a how-to guide on creating one’s own blackout poems. He offers some examples submitted by readers of his blog. “Think you’re not a poet?” Kleon asks, challenging his readers to put down his book and make their own blackout poetry. In fact, the best thing about this book is its insistence that poetry is for everyone. “Writing should be fun,” Kleon remarks in the preface, “Everyone can do it. I hope this book inspires you to try to create your own blackout poems.”

So, will this book change your life? Probably not. Is this book fun to flip through? Yup! Will it make you want to try your hand at blackout poetry? Absolutely! While Newspaper Blackout won’t make serious waves in literary history, it is a pleasant read for a summer afternoon and might just be the gateway to poetry for some reluctant writers.

Amelia Cook, after spending her twenties exploring warmer places like Honduras, Ecuador, and

Tybee Island, has returned north and is settling in to her third decade of life in her home state of Wisconsin. She spends

her days as Assistant Director for International Admissions at Madison’s Edgewood College and her evenings freelancing

and teaching creative writing. Since 2007, she has been a regular contributor to Isthmus, Madison’s arts and

entertainment weekly, covering local theater and other miscellany. Her earthly pleasures include Friday night fish fries,

This American Life, and sharing a pitcher of Spotted Cow Ale with friends and family. She is pleased to be

pursuing her MFA in poetry through the University of New Orleans.