REVIEW

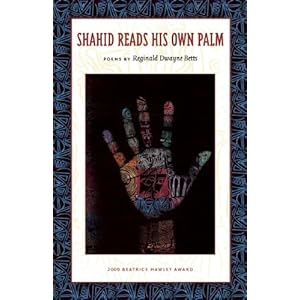

A Review of Reginald Dwayne Betts' Shahid Reads His Own Palm

Shahid Reads His Own Palm by Reginald Dwayne Betts

Alice James Books, 2010 (80 pages)

ISBN: 978-1882295814

Alice James Books, 2010 (80 pages)

ISBN: 978-1882295814

Music playing on car radios, a poster of a beautiful woman, and prison yard weights all play important roles in the world Reginald Dwayne Betts introduces in his debut collection, Shahid Reads His Own Palm. These poems open a world of rigidity with a tenderness that goes unseen by the general public when it comes to prisons and those incarcerated.

Betts, in the title poem, outlines what we can expect from these poems, introducing us to "men who arranged their lives around the mystery/ of the moon breaking a street corner in half."

Prisoners, family members, and friends are given voice as the collection traces histories both ancestral and institutional. These are urban prophecies, stories from and about a myriad of characters that have seen hardship, but pursue life as strongly as any free person nonetheless.

"How to Make a Knife in Prison" is an example of an activity becoming something more:

Lockdown

brings him to his knees.

His hand palms

the scrap like a preist

about to carve

a god.

Betts offers character portraits, how to poems, odes, and elegies with specificity and clarity. The diction is working class, filled with slang and colloquial phrasing. We begin to learn about these people and see them more clearly as Betts describes the scenes they inhabit.

Rather than focus a negative light on prisons and correctional institutions, Betts explores extraordinary circumstances that stand out in their beauty among such hardened, gritty surroundings. A kind of tenderness emerges in "Fantasy Girl," where the speaker is sodomizing another inmate in a brutal fashion, yet hints at a closeness and almost affinity for the other boy in the descriptions of him. Jeremy, the recipient, is a "knife-slim/ boy" and when his body goes limp, after the speaker finishes, he is laid in bed almost like a parent might tend to a child.

While Betts brings the poem to the edge of violence, there is restraint in the tone and texture of the voice: he doesn't simply fling the boy off or demean him further, but instead takes time to "lay him in bed." Affection, here, is at a premium and Betts allows a look in on one moment where it is both given and received, even when a horrible act might be perceived to be taking place.

For all of this tenderness, though, there is pain, suffering, and violence along the road. Not all things keep "razors/ from plucking away at the flesh covering a vein," nor do they stop one from admiring the that vein, ripe for the plucking:

Straight up, the curve of a wrist is beautiful,

majestic, another reason to open your heart.

& if this is ridiculous to you, I understand.

There is a day that none of us knows

anything about & it could be a Thursday

& this is all the reason you need.

Betts is adept at carving out the body, finding feeling where only flesh should reside. "There are ways/ a man is tortured that only he can tell you," he writes, in "An Opened Vein." And, though it seems opposite the goal of this collection to admit that, the truth is in each character's soulful storytelling, their quiet, yet full recognition that there is something more in this prison than bad men acting badly.

Taylor Rickett received his MFA in Poetry from Drew University. His poems have appeared or are

forthcoming in NEBO: A Literary Journal, Stone Highway Review, and Naugatuck River Review, among others.

He resides in Bloomington, Indiana where he works as a kitchen manager.