REVIEW

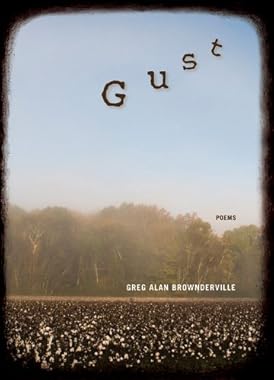

A Review of Greg Alan Brownderville's Gust

Triquarterly, 2011 (136 pages)

ISBN: 978-0810152212

Greg Alan Brownderville is far from the first poet to confront contradiction, and his first collection, Gust, is certainly not the first book to embrace it. Contradiction and conflict have lain at the heart of poetry for centuries, before Whitman "contained multitudes" or Ginsberg saw himself naked in the Negro streets. Like the two poets from whom he draws inspiration, Brownderville gamely throws himself into a variety of perspectives and paradoxes: an Italian immigrant turned black food vender, a choir boy voodoo apprentice, an overly elegant and poetic lawman. Yet Brownderville, an Arkansas native, is not content to simply separate these disparate identities, nor does he seem interested in resolving them. Instead, he gives each contradiction room to breathe and grow, his quest "to make my life a simple yes, / but to a complicated question." There is an emphasis not on conflation but on acceptance, of letting life come to him as it will.

Gust is a book not just with stories but about them - about what it takes to create them, what it takes to tell them, how they shape us, and how they can ultimately transcend us. It is a fascinating first book possessed by God, the Devil and more, whose cries to be heard break the plains of music, prose, poetry, with a bluesy holler.

Like the prelude to a novel, "Press In" is a both a call to listen to Brownderville's tale and a hint of the themes and stories to come - death, sex, spirituality, art, colorful characters. What follows is the first of many narrative and thematic arcs, beginning with a speaker's birth, ("Dark Corner") and ending in a death ("Last Song for Brother Langston"). Though the comparison seems obvious, Brownderville takes some cues from Faulkner by crafting his own "postage stamp" of southern land, and sticking to it, exploring every dark, semi-biographical corner. The poems in this first section bask in their contradictions, as coming-of-age rituals of Vodou and Christianity collide back to back ("Telephone" and "Soul-Selling Ritual") as if they were cut of the same cloth. Ironically, it is Brother Langston, epitome of the Church, who calls us all together despite our differences: "'I don't keer / if you're a sinner man or woman or a holy saint of God — / come on people, press in!'" The speaker fits in neither category, and yet the poems rest comfortably in both worlds. "Lord Make Me a Sheep," Gust's powerful thesis statement of sorts, slides effortlessly between poetry, conversation, soliloquy, and teleplay while painting the illusion of biography. In the poem's final passage, a stanza that could have been a lost page from "Leaves of Grass," Greg asks the Lord to transform him into a list of objects, immediately owning up to the contradictions his audience may be objecting to. His final cry to "make me a sheep" is multi-layered and poignant - perhaps he means a real, physical animal like his brother (who humorously takes the sermon literally); perhaps he means an agent of God; perhaps he simply wishes to be carefree, to follow whatever path calls him, as if carried by a gust of wind.

Free of the constraints of contradiction sown into the first section, in the "Wild Yonder Blues," Brownderville sets off to explore the world, growing and building a voice from the bits and pieces presented by "Press In." The first two poems of the section are radical departures from the first section, as Brownderville breaks down his conception of poetry with humor and daring. Like a teenager flirting with newfound freedom, "From a Nationally Televised Press Conference..." pushes metaphor, elevated imagery, and poetic cliché to its brink while continuing the experiment with the theatric structure first seen in "Lord, Make Me a Sheep." The following poems range from Wallace Stevens-inspired observation ("The Palm Tree Soliloquies") to prose segments ("All of This..."), to traditional Zimbabwean metrical patterns ("Sex and Pentecost"). The experimentation gives "Wild Yonder" its narrative drives, growing and expanding along with the poems, whose themes of sexual awareness and religious wandering reinforce the wander nature of the section. Gust's central drive is an exploration of voice and tone, not necessarily of Brownderville or his poetic doppelganger, but of the book as a whole. The jarring vocal shifts recall the Vodou rituals of possession, and underscore the shifting perspectives and practices that litter the poems. These deviations from "normal" poetry come at times of critical importance and shifting perspective: in the midst of spiritual conflict, calamitous weather, or simply getting high.

This becomes abundantly clear in the gorgeous third section "Becoming Hot Tamale Charlie," when Brownderville breaks from his newly developed voice to inhabit Carlo Silvestrini, dramatizing his rough life out on the page. Raised in "in the habanero heat of Delta summer," (a fantastic line that would not be out of place in a song by guitarist Robert Johnson) Carlo feels the stench of death, the lightness of love, the pain of spiritual longing, and the blues of rejection in quick chronology. It is as if Brownderville synthesized all of his wandering blues into a single soul and gave it a name. Eventually, that persona too grows into something new, and when Carlo says that "I decided to become a colored man," there is a brief and bizarre moment where writer and character become one and the same. Like the man who created him, Carlo is not constrained by his former self, and sheds the skin to adopt another persona that better suits his story, continuing the cycle of creation begun by Brownderville. As ephemeral and shape-shifting as the volatile Vodou loa, both Brownderville and Carlo/Charlie are actors, inhabiting the role that best fits their growing mythology.

Formally, Brownderville calls on musical history to complement his rhythmic verse and spiritual wandering. Under the surface of the Vodou/Christian conflict brews a battle between gospel and the blues, yet much like the religious debate, the two are more compatible than they first suggest. Music provides linkage from young to old ("Last Song for Brother Langston," "The Magic of Song"), man and nature ("She Dances with Tornados"), singer and audience ("Goblin Song"). More importantly, it provides a powerful emotional framework for the book as a whole. While said somewhat tongue in cheek, Brother Langston means it when he declares that "I've seen more people saved / through my singing than my preaching." The music provides the drive, heart, and soul of religion, and it is ultimately the only thing that keeps the speaker coming back to his Christian roots ("Last Song). The Gospel hymns Brownderville chooses are keenly picked songs about transcendence ("I'll Fly Away," "Higher Ground"), but are also subtly dark ("Power in the Blood"). This undercurrent of hope and joyous celebration provides a crucial counterweight to the death and darkness that often threatens to overpower the poems. By turning to music, Brownderville gives death an optimistic spin, crafting it into a chance to join the Lord in song.

And yet this, the turning of deepest despair into smoldering expression, has long been the providence of blues, a genre that takes a hold of Gust and never lets go. The music stands not for an idea or philosophy but for people, for stories of living, dying, singing, and crying. Throughout the ages, the blues have become not just a genre but a badge of honor, meant only for those that have really, truly, felt the blues. Civil Rights activist Alberta King's supposition that, "Blues is what the spirit is to the minister [...] We sing the blues because our hearts have been hurt, our souls have been disturbed" could not fit more perfectly with the down-low, back to back agony of "Jook House in Burning Season," "Goblin Song," or "Hot Tomale Charlie Sings of a Player's Heartbreak." The blues provides the structure of expression and storytelling that bleeds through Brownderville's rhyme and rhythm. Some poems, like the Muddy Waters sampling "Honey Behind the Sun," wear the blues aesthetic on their sleeve: "Trombonists blow their melodies cheek tight / and loose them like balloons / untied and yellow bright" (13). Others hide it under the surface, like the loose irregular rhyme of "-ill" in "The Mysterious Bar-B-Q Grill" and numerous other slant rhymes and syncopated rhythms throughout Brownderville's melodic, slinking verse. Some form of the blues touches every poem, running alongside Gospel to give Gust its emotionally charged, soulful soundtrack. This heavy borrowing from music gives the poems their breathless quality, because whether its blues or hymnals, both genres come from a tradition of unstoppable expression, of stories and prayers that have to be sung.

Ultimately it is art itself, regardless of form or content, which has real, raw power, so long as it sings its stories from the heart. These are the "Ghosts" of the final section, the myriad inspirations and songs swirling around every story or poem. Like the mysteriously passed-on BBQ grill in the final poem, Brownderville can't hide his dirty, mismatched past "in the backyard or the shed / it's smack-dab in the front or it gets mad." The grill becomes a symbol of every ghost and memory once shared or forgotten. It is alive, familiar and a little menacing, but what it ultimately provides is food. The grill, like Brownderville, takes those memories, stories, and pork shoulders and cooks them into sustenance, as if the stories are necessary for basic survival. In Gust, perhaps they are.