REVIEW

A Review of Natalie Giarratano's Leaving Clean | Katherine Hoerth

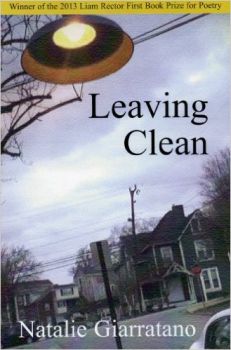

Leaving Clean by Natalie Giarratano

Briery Creek Press, 2013 (63 pages)

ISBN: 978-0982488041

Briery Creek Press, 2013 (63 pages)

ISBN: 978-0982488041

In poetry, we often think of the grotesque as a spectacle, with the poet playing the part of the observer, a distant narrator. In her latest collection, Leaving Clean, Giarratano, however, places her speaker in the midst of the landscape of Texas bayou country, and uses this as a vehicle to describe the complexities of a fragmented family history, of an at once broken and whole self. The result is an honest, raw, and hauntingly beautiful collection of poems that pushes the boundaries of American poetics, making us see the beauty in the ugliness, the intricacies of where we come from and who we are.

Poetry of place makes up a good portion of this book, meditations on how the land itself is a contradiction of sorts, a thin veneer of slack water covering generations of sin, violence, and loss. The poem, "Orange, Texas" opens up with the speaker describing her hometown's "liquid earth," the "wind that rushes through their reeds / giving … a voice, and it says / with little confidence: I am not soulless." The poem goes on to describe the absurdities of the landscape's past that is just beneath shallows, how the "slaves are still / dancing near the surface," that "once dwelled in the water. tired of not being people before / they become sacrifices for alligators;". The speaker makes us look closely at the gray "in the air, the buildings, the light, the people" that "all stink of forgetting." But the speaker won't let us forget or look away. In "Slack Water Lullaby" readers, along with the speaker, are steeped, almost baptized into the land itself, its "black obsidian / slick" with "cold / reptiles," "tall weeds," and "mold / caked on" her feet that won't wash clean. The poem closes with the landscape becoming a part of the speaker herself as she declares: "I breathe in bog."

The landscape, though, plays an important role as a vehicle for the speaker to describe, too, the complexities of her familial relationships. A number of the poems explore the speaker's relationship with her father, whose presence and influence is, itself, a sort of haunting. For instance, "Firecracker" describes a father who believes Charles Manson was brought by aliens "to do the deeds no person would do," and watches serial killer flicks with his young daughter. The poem, mimicking the form of a sonnet, turns with the realization that he's a part of her: "you realize just how fucked up you might / get." Other poems intertwine familial dysfunction into the landscape itself, so much so that there's seamlessness between tenor and vehicle. "Hustle" opens with an image of "A human advertisement" — the statue of liberty — which reminds the speaker of "that red and white / Ford truck you left upside-down on the side of the road." The poem unfolds into this narrative of a drunken father who crashes the truck, leaves it there "mixed in with the armadillos on a shoulder / of the road, let the world know // you're a drunk." After this stark announcement of dysfunction, the poem blurs into the speaker's own drunken dreams of her father transforming into "a gorilla that rises / from the ground with flutes of champagne" or "getting remarried" to a "good girl who doesn't ask questions and doesn't / speak English." The poem closes with a particularly grotesque image of the father's dysfunction merging with the muddy landscape:

Then you crawl through the wrong

Texas wetlands to search for

What you don't remember losing on one of the nights

You were almost a criminal.

This haunting, too, is something that the speaker cannot escape. It's there, just beneath her skin, just like the sins of the past still cling to the land itself. The collection's opening poem "Self-Portrait as a Pair of Shoes Hanging from a Power Line" places the speaker right in the middle of it all, not as a casual observer, but as a reluctant participant, a part of the town itself. "Notice us not because / you have to;" the poem begins, calling out to the readers to see the contradictions and surreal absurdities around them — the "white / flowers on the church lawn // on which a dog daily pisses," the woman who "carries a knife because // she dreams of a faceless stalker — / could be Jesus," or the "easy town" where "everyone is semi-automatic." These strong, crafted images echo the emotional truths of contradiction and complexity set in a landscape of ugliness with beauty.

Essentially, these are poems that don't let us forget; they don't let us look away the grotesqueries of everyday life. In the collection's eponymous poem, "Leaving Clean," the speaker tries to escape her past, her hometown, and essentially, her own self in Prague where "you don't have to hide from the sun." But home creeps into even the smallest of moments, when a plastic owl's feathers, "painted by a blind woman or a five-year-old … matches the soft afghan my mother knitted for me decades ago," or when she visits the basilica that's "straight up sold-out of Jesus" where she remembers how she "drank holy water from a pink / and blue Mary and how it made me feel clean / like messages the rain had been leaving me for years." Her past is a part of her, and she realizes this in the closing lines: "It's then I know there is no map I can buy / to show me the way out of here."

Giarratano is brave and skillful poet, one pushing the boundaries of what her craft can achieve, showing us both the light and the shadow of who we are. She places her readers knee-deep in the bayou, and the result is a portrait of both the self and the land that is at once ugly and lovely, broken and whole, painful and therapeutic. The grotesque is in us all, and Leaving Clean is a testament to the contradictions, absurdity, and beauty of contemporary American life.

Katherine Hoerth is the author of three books of poetry: a collection titled

The Garden Uprooted (Slough Press, 2012), and two chapbooks titled The Garden of Dresses (Mouthfeel Press, 2012)

and Among the Mariposas (Mouthfeel Press, 2010). She teaches writing at South Texas College, and edits poetry

for Fifth Wednesday Journal.