REVIEW

A Breathless Flood:

Amie Whittemore's Glass Harvest | Dorothy Chan

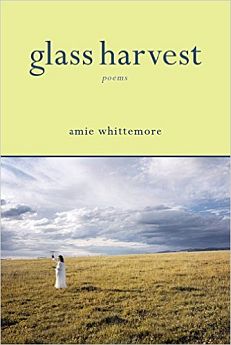

Glass Harvest by Amie Whittemore

Autumn House Press, 2016 (78 pages)

ISBN: 978-1-938769-16-0

Autumn House Press, 2016 (78 pages)

ISBN: 978-1-938769-16-0

Amie Whittemore's debut poetry collection, Glass Harvest, is filled with this essence of "deluge," from a literal deluge one thinks of when building a metaphorical ark in "Dream of the Ark" to a flood of passion one feels when leaning in for a lover's kiss in "Blackberry Season," "Charlottesville, 7 a.m.," and countless other poems. Whittemore's aesthetic is ecological—she looks into the relationships between people and the nature surrounding them. For instance, in her opening piece, "Aphorisms," she creates beautiful metaphors connecting growth in a person to natural gain: "If you can admit your own narrowness,/you're onto permission and cardamom./If you dust off your brave pants, you'll

manage/mudslides, samba, dodge and weave./The smallest voice is the truest;/wear those ears that turn like planets." I enjoy how Whittemore equates these metaphors to "aphorisms." By doing so, she is not only challenging her reader to seek out these truths, but also wants to change their mindsets to become more ecologically minded. Yet, besides this erotic-ecological backdrop, Whittemore's book is filled with other forms of passion and love: a woman who desires other women, a speaker who pays homage to her grandmother and who tries to continue this lineage with a letter to her future granddaughter, and above all, a voice that finds the erotic in the intellectual.

This "erotic in the intellectual" is inherent in "Blackberry Season," one of Whittemore's standout poems. Whittemore's playfulness in language is brilliant: "We toss blackberries at each other's mouths/as if they are tiny grenades—". This playfulness is also sensual: "The tilt of your chin/makes me think you mean red velvet cake/when your beer and berry breath leans/in for a kiss. Not once have you asked/to touch the eggs, though they are smooth/as the word yes, heavy as no." Here, the "intellectual" includes an analysis of language—while "yes" is smooth, "no" is heavy-and with this, Whittemore has gained another aphorism. This is then balanced with the visceral and even tragic: "Blackberry seeds/turn our tongues to sandpaper and my skirt/thrown across the floor looks like a lake/where a child has drowned." By including a poem about blackberries, Whittemore inserts herself into a "poets writing about blackberries" tradition that ranges from Sylvia Plath ("Blackberrying") to Robert Hass ("Meditation at Lagunitas").

The lines, "Your set to work,/turning our bodies into jam" in "Blackberry Season" is comparable to "My mind's oatmeal again" in "Crush." In "Crush," Whittemore utilizes the short lines to her benefit in order to create a tension and release of sensuality: "rose petals clamping my throat,/the end of this sentence not resulting/in your body pressed against me,/so I'll abandon it for—". The em dash after "so I'll abandon it for—" is brilliant—it allows for the moment of breathless hesitation after one body touches the other.

Whittemore's poems also play into female sexuality. For instance, in "Charlottesville, 7 a.m.," the speaker juxtaposes the image of her husband speaker with the synesthesia of a woman's lips: "The woman's lips—soft and tough as a fox's padded foot./It arrives now, bloodstain on a gray hood./It tests the earth like morning." These are the last three lines of the poem, making it both resonant and clear that the speaker is yearning for the female stranger rather than her husband. The way the speaker reminisces about the woman's lips is telling. Though the woman's lips are soft, their effect is like "bloodstain" which "tests the earth like morning" when the speaker is back with her husband. For this reason, the ending line becomes all the more haunting.

As much as Whittemore pervades her collection with sensuality, she also juggles with lineage and family history. I love Whittemore's wordplay of "widow" and "window" in "Two Windows." Above all, poems like "Two Widows," "First Visitation," and "Second Visitation" pay beautiful homage to her grandmother. The poet not only continues this lineage with "To My Future Granddaughter," but she also rewrites this lineage. She, the poet, takes control of this history: "You're afraid that's all./It's stupid we're built this way—". Colloquial asides such as this really ground the poet's point-of-view with the reader's. With this, Whittemore is telling both her granddaughter and the audience that we're all "afraid," but that's why we have each other to reveal our deepest secrets to. Whittemore has revealed some deep secrets, yet she still ends on a lighter note, which brings the reader in even more. "Switchgrass" balances this lightness with again, the intellectual: "Though it intimates intellectual laziness,/as well as, perhaps, perversion, I'm a little hot/for your Wikipedia entry." Whittemore has rolled intellect, eroticism, secrets, and even perversion into another bold statement, leaving us craving more of her secrets in this "glass harvest."

This "erotic in the intellectual" is inherent in "Blackberry Season," one of Whittemore's standout poems. Whittemore's playfulness in language is brilliant: "We toss blackberries at each other's mouths/as if they are tiny grenades—". This playfulness is also sensual: "The tilt of your chin/makes me think you mean red velvet cake/when your beer and berry breath leans/in for a kiss. Not once have you asked/to touch the eggs, though they are smooth/as the word yes, heavy as no." Here, the "intellectual" includes an analysis of language—while "yes" is smooth, "no" is heavy-and with this, Whittemore has gained another aphorism. This is then balanced with the visceral and even tragic: "Blackberry seeds/turn our tongues to sandpaper and my skirt/thrown across the floor looks like a lake/where a child has drowned." By including a poem about blackberries, Whittemore inserts herself into a "poets writing about blackberries" tradition that ranges from Sylvia Plath ("Blackberrying") to Robert Hass ("Meditation at Lagunitas").

The lines, "Your set to work,/turning our bodies into jam" in "Blackberry Season" is comparable to "My mind's oatmeal again" in "Crush." In "Crush," Whittemore utilizes the short lines to her benefit in order to create a tension and release of sensuality: "rose petals clamping my throat,/the end of this sentence not resulting/in your body pressed against me,/so I'll abandon it for—". The em dash after "so I'll abandon it for—" is brilliant—it allows for the moment of breathless hesitation after one body touches the other.

Whittemore's poems also play into female sexuality. For instance, in "Charlottesville, 7 a.m.," the speaker juxtaposes the image of her husband speaker with the synesthesia of a woman's lips: "The woman's lips—soft and tough as a fox's padded foot./It arrives now, bloodstain on a gray hood./It tests the earth like morning." These are the last three lines of the poem, making it both resonant and clear that the speaker is yearning for the female stranger rather than her husband. The way the speaker reminisces about the woman's lips is telling. Though the woman's lips are soft, their effect is like "bloodstain" which "tests the earth like morning" when the speaker is back with her husband. For this reason, the ending line becomes all the more haunting.

As much as Whittemore pervades her collection with sensuality, she also juggles with lineage and family history. I love Whittemore's wordplay of "widow" and "window" in "Two Windows." Above all, poems like "Two Widows," "First Visitation," and "Second Visitation" pay beautiful homage to her grandmother. The poet not only continues this lineage with "To My Future Granddaughter," but she also rewrites this lineage. She, the poet, takes control of this history: "You're afraid that's all./It's stupid we're built this way—". Colloquial asides such as this really ground the poet's point-of-view with the reader's. With this, Whittemore is telling both her granddaughter and the audience that we're all "afraid," but that's why we have each other to reveal our deepest secrets to. Whittemore has revealed some deep secrets, yet she still ends on a lighter note, which brings the reader in even more. "Switchgrass" balances this lightness with again, the intellectual: "Though it intimates intellectual laziness,/as well as, perhaps, perversion, I'm a little hot/for your Wikipedia entry." Whittemore has rolled intellect, eroticism, secrets, and even perversion into another bold statement, leaving us craving more of her secrets in this "glass harvest."

Dorothy Chan was a 2014 finalist for the Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Poetry Fellowship and a 2016 semi-finalist for The Word Works' Washington Prize.

Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Blackbird, Plume, Spillway, Little Patuxent Review, Dialogist, and The McNeese Review. Her poetry has been nominated for a Pushcart.

She is the Assistant Editor of The Southeast Review.